All installments Part 1 || Part 2 || Part 3

I recently had an experience while out to dinner with a friend that got me thinking about this series, and about an installment I knew I needed to tackle but wasn’t sure how to start. A song came on the overhead speakers, and my first thought was: A-pop! And then my second thought was: well, not quite A-pop! It turned out to be a song I’ve heard before, from an artist I know: MUNA’s “What I Want” from 2022. A few songs later, I had the same experience. A-pop! Or…almost A-pop? It was another artist I recognized whose song I couldn’t name: Clairo’s “Bags” from 2019.

This experience kept happening, distracting me from my conversation while I discreetly tapped the Shazam button: Julie Jacklin, “I Was Neon.” Del Water Gap, “Better Than I Know Myself.” After about a dozen of these sorts of songs, the staff finally changed the music over to a Bad Bunny playlist, instantly changing the mood, or at least my mood. No more uncanny flashes of recognition from music that sounded caught halfway between adult contemporary radio and indie rock. Was this an A-pop experience? What do you call this music?

Ten or fifteen years ago, in the heyday of artists like Robyn and Carly Rae Jepsen uniting indie audiences and certain subsections of mainstream pop audiences, I’d just call it all indie-pop. The indie scene that I grew up with and cut my teeth as a music critic reviewing in the ‘00s had already been converging with mainstream pop scenes for many years.

I believe the primary engine of this convergence came not just from the indie side, but from lowering expectations of pop music, especially in the album marketplace. Music critics have been describing the convergence of pop and indie for decades now. In a 2004 write-up of Pitchfork’s song of the year, “Heartbeat” by Norwegian pop act Annie, Scott Plagenhoef wrote a pithy state-of-the-scene capsule that’s worth quoting in full:

With Modest Mouse, Franz Ferdinand, Garden State, and “The O.C.” opening doors for small bands to earn some mainstream respect, 2004 is being considered by some publications to be the year that “indie” ceased to be shorthand for “independent”; just as likely, it could be the year that “pop” ceases to be derided as merely short for “popular,” as it saw MP3 blogs and other internet outlets paving new, industry-free avenues for should-be worldwide hits from artists such as M.I.A., Rachel Stevens, The Knife, Fox n’Wolf, Ce’Cile, Scissor Sisters, U.S.E., Slim Thug, PAS/CAL, Lady Sovereign, Love Is All, Johnny Boy, and Girls Aloud, among others.

The best of this new wave of fluxpop—tracks with a pop sensibility and communicative, crossover potential that are nevertheless more often transferred via 0s and 1s than Hot 97s or Radio Ones—is Annie's “Heartbeat.” Annie’s encapsulation of anxious moments and the thrill of possibility and simple pleasures hasn’t yet had the chance to become a proper hit; it was issued as a promo this year and will be given a full UK release in February. For now, it’s a quiet success, which is fitting for this shy slice of bundled nerves and nervous energy. Without striving for any of the benchmarks usually associated with year-defining singles—say, barrier-crashing innovation, or spearheading a new genre— “Heartbeat” achieves the very rare feat of simply being a perfect pop song, as well as the arbiter of a very new means of discovering classic pop tracks.

Parts of the blurb are dated—MP3 blogs are long gone, and I don’t think I’ve heard even passing reference to Fox N’Wolf since 2004. But pairing the observation that “indie doesn’t mean independent anymore” to the corollary phenomenon “pop doesn’t mean popular any more” is prescient.

Robert Christgau has referred to under-the-radar pop music that isn’t extremely popular but also isn’t always derived from indie’s lineage—post-punk, college rock, alt-rock—as “semipopular” since 1970. Christgau’s semipop is a broad description of popularity below mainstream levels that nonetheless has some “pop” cachet. You might call it a submainstream—always alongside or with nominal aspirations to widen into or join the main. “Indie” has usually been a more determined sidestream, defining itself (at least in part) in opposition to the main.1

The historical widening and narrowing of different streams in the past twenty years or so is a common conversation topic among the pop commentariat online, often annoyingly discussed in terms of a mythical former monoculture. I’m against using this term—if you formulate it as “monostream,” you get an immediate sense of why the term doesn’t work. Unlike mono-, main- is always a flexibly relative designation. In the same way that mass culture can compel the question “whose mass” or “how big” without an implication that the mass means everyone, mainstream always suggests other tributaries.

What I think is undeniable, though, is that the transition to the global celestial jukebox has scrambled a lot of streams—some formerly minor streams are much more main, while other former mains are practically reduced to a trickle. Plenty of streams are still big, of course, yet nonetheless maybe feel smaller with so many other streams to compare them to.

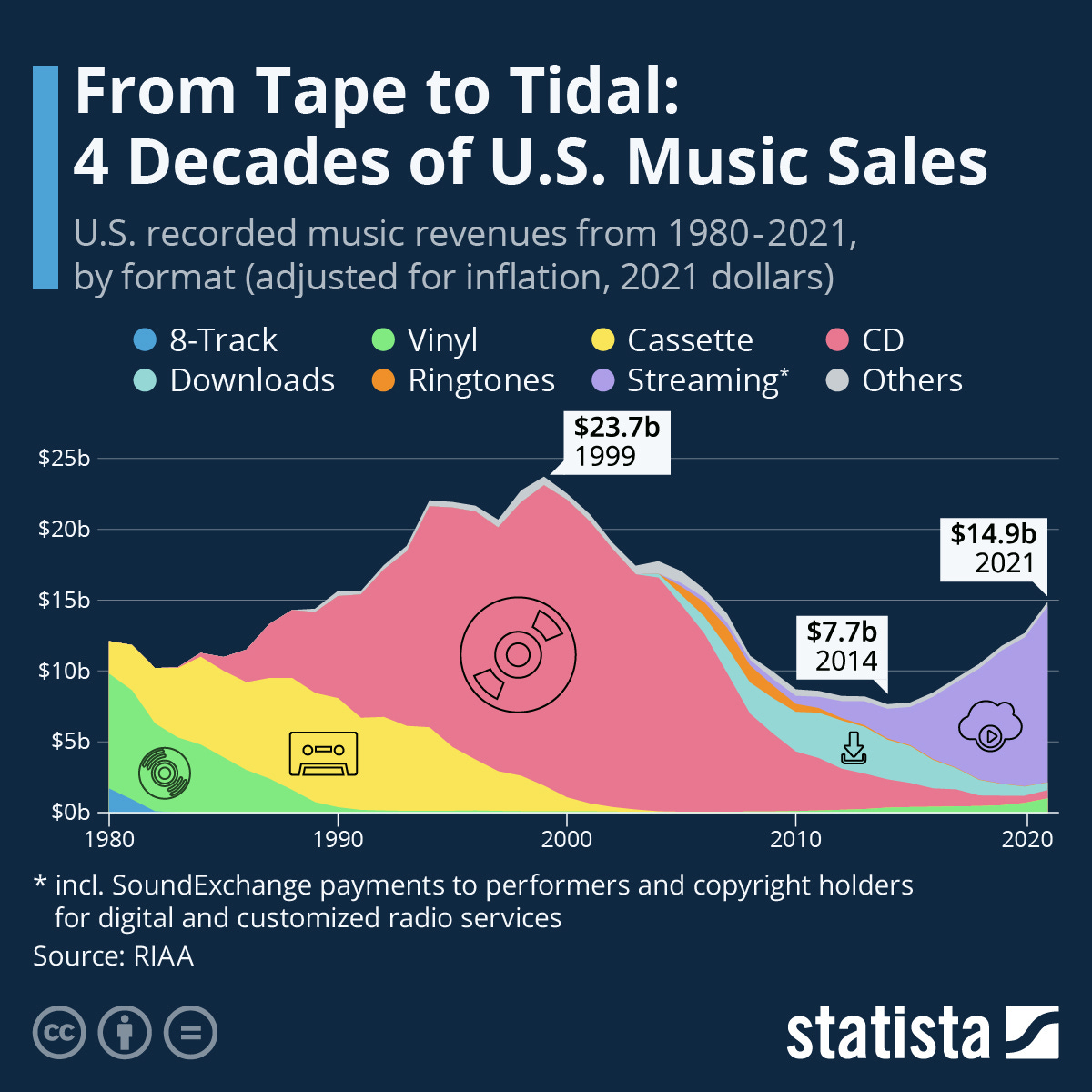

The mid-aughts era of pop in flux suggested a sidestream widening into a something resembling a mainstream, becoming a dominant flow of mass culture. I think it’s important to remember the backdrop to this seeming expansion: the mid-aughts were also a period of precipitous industry contraction. Looking at the big-picture trajectory of US music sales is instructive:

The definitional hardening in the early aughts of “indie” as a term distinct from other formulations happened at a time when physical music sales were cratering with no wider cultural sense that this could be meaningfully stopped. One reason indie began to uproot from “independent” is not just that lots of indie-style music was succeeding on major labels, but that lots of major label music was doing indie numbers.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the moment of peak uncertainty in the sales landscape — i.e., the point at which streaming is not yet a major revenue generator but physical sales are reaching generational low points while digital downloads can’t make up the losses — happens to be between 2006 and 2011. 2011 is the year Spotify launched in the US and major labels went all in on a digital protection racket and/or suicide pact (no one really knew which would come to pass at that point).

In 2009, the end of the Before Times, music critic Chris Weingarten coined the acronym GAPDY, which stood for the five indie darlings whose albums he predicted would dominate critics polls that year: Grizzly Bear, Animal Collective, Phoenix, Dirty Projectors, and Yeah Yeah Yeahs.2 Had indie arrived, or was everything else departing?

The second half of the aughts was a sales freefall—of album sales in particular—that for the first time made indie rock music consistently competitive in the album charts.3 Starting in about 2006, most major indie releases buzzed about in year-end polls also hit the upper reaches of the Billboard 200, with some critically acclaimed ones getting near or even inside the top ten (in 2009, Animal Collective went to #13 and Grizzly Bear went to #8). The upheaval of this leveling process arguably peaked in 2010, when Vampire Weekend and Arcade Fire both had #1 albums, and Arcade Fire won the Grammy for album of the year.

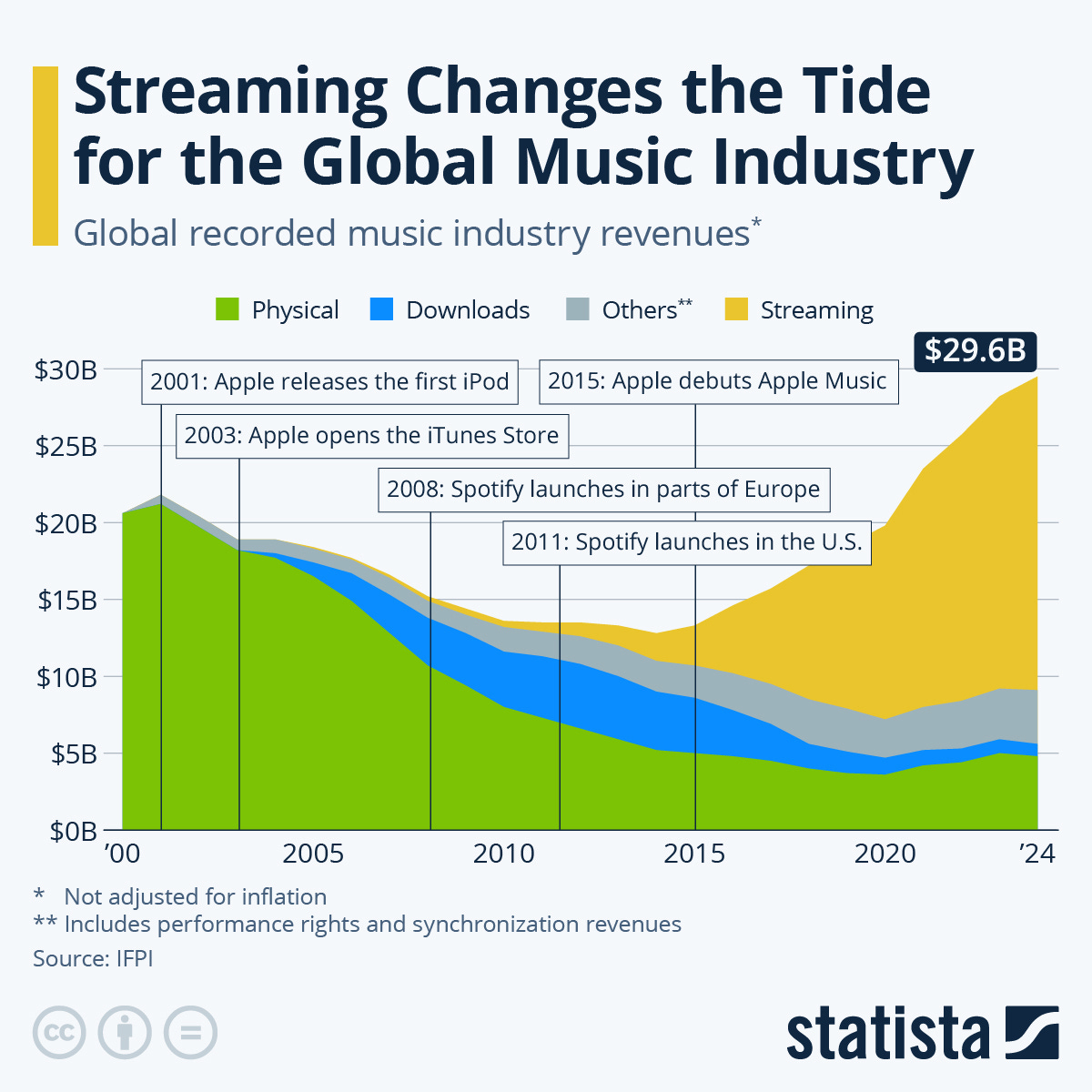

What happened after the great leveling was the emergence of streaming as the only way for the recording industry to recoup its revenues. They did recoup them, mostly by making the vast majority of back catalogs available on streaming services at the expense of all other formats, including the ignominious crash of digital downloads. You can zoom out to global music sales and see that streaming has now matched the revenues of physical formats 25 years ago at the peak of the CD bubble, while physical sales are comparable to downloads at their peak and downloads have effectively vanished:4

This provides a handy visualization to my claim in the first part of the A-pop series that the technological changes underlying the globalized streaming environment are probably as much of a causal mechanism as you need to explain why the long tail of American pop might pale in comparison to the collected output of the rest of the world. This is especially true in a monsterverse environment where super-streamers account for an inordinate share of streaming revenue.

The transition to a global streaming era has also accelerated the blurring of lines between indie and pop. The end result of this process, I think, is not really a new mainstream or a larger separate sidestream, but a sort of middlestream. “Mainstream pop” has become a genre distinction (that is to say, A-pop) and has atrophied, while indie pop has toned its little muscles. What you get is an indie/pop music that has merged and mutated over the course of a decade, like the botched transmogrification in David Cronenberg’s The Fly. The transporter zap is the fall of physical media and accompanying rise of indie as a main-ish-stream force. Now this process has reached its climax, and we’re dealing with a gnarly monstrosity, albeit an exceedingly pleasant-sounding one that sounds fantastic in coffee shops.

What I find odd about this awkward middle point between indie and pop is that the music has a house style with immediately identifiable sonic features, as though the whole field from top to bottom has figured out what it’s supposed to sound like, but there are still barriers between the chart successes and the below-the-radar ecosystem. This was not really the case during the indie boom of the mid-aughts, which featured meaningful, if sometimes minor-seeming, factional disputes between different types of indie music, and few of these strands seemed directly connected to chart pop, though some of the songs wound up on the charts, and some indie artists shaped sounds and production of chart pop through the ‘10s as influences and producers.

Middlestream music is mostly (but not exclusively) made by women, with a casual indie backing band of guitars and synths. It tends toward gauzy production with discernible (but not too memorable) pop hooks in the chorus. The lyrics are lightly confessional, but performers aren’t too hung up on getting words across. The music is informed by pop but not fully of pop. It is A-pop-ish—the fluxpop of 2004 softened into mush-pop twenty years later. I often refer to music like this, from nobodies and huge stars alike, according to my visceral sense of its consistency: mushy, slushy, globby, blobby, goopy, gloopy, soup.5

This is the sort of indie-pop, or indie/pop, I was hearing at dinner. I hear it constantly: in boutiques, in coffee shops, in restaurants. At least ten or twenty tracks like it have shown up in the playlists I skim for new songs each week for years. Spotify is very good at recommending it.6 Here’s a playlist that I seeded with only the four songs I heard playing at that restaurant, and then just added every name I didn’t know or couldn’t place despite vaguely recalling the name, until I hit 100 different artists.

I know this music when I hear it, but am not satisfied that it has a distinctive enough name. Spotify’s encoded genres list only “indie pop” or “bedroom pop.” But both terms seem too broad. A huge swath of music that sounds nothing like this is made in bedrooms all over the world. “Indie pop” is closer, but seems to also include too many other types of semipopular music that don’t sound like this.

Friends at the Singles Jukebox, which has spent many years covering, theorizing, and otherwise cataloging indie pop, have recommended the following genre names:

Panera pop, after the Panera chain’s playlists;

Topshop pop, after the British fast fashion company;

Yearncore (from Hannah Jocelyn, who should write about this!); and

Window pane, my personal favorite, which describes the vague sense that you’d listen to these songs while gazing out a car window, brooding a bit, but also feeling a glimmer of rising hopefulness of something new on the horizon.

I’ve also heard this music referred to as streamcore.7 This is a shorthand used by people whose conspiratorial focus on the machinations of streaming platforms seems oddly picayune compared to the global shifts that streaming has actually engendered—like greeting the invention of the radio with crossed arms because of local DJ payola schemes. This explanation claims, not very convincingly, I think, that window pane is the sort of music you can put on in the background, and so lots of people make it specifically to get it put on in as many backgrounds as possible.

But the music itself is not intentionally designed to be played in the background. It’s not Muzak. The genre’s performers tour and build fanbases and do all the normal music career stuff. Some of them do well in music publications and critical polls, though not many of them. A few of them are actual pop stars, or at least have potential, and nearly all of them are at least trying to be actual pop stars.

The better term for the deluge of this music is probably the same epithet applied to certain indie music in the UK when it reached a particular saturation point: landfill. “Landfill indie” referred to a British post-punk variant of indie that never had as much traction in US indie scenes: bands like Razorlight, Maxïmo Park, Editors, and Glasvegas, among about a hundred others.

To some extent, window pane is just landfill indie-pop. What I think is different, though, is how little daylight there is between landfill and promised land. The musical palette of window pane is technically close to the tropes and conventions of A-pop. But there is that stubbornly immovable plate of glass between the two. The automated playlist recommenders seem certain that I’m not looking for major players when I add this music to my playlists—even Boygenius, the indie rock supergroup trio styled for Rolling Stone as an alternative breakout like Nirvana and seemingly the apex of the window pane style, hasn’t shown up yet, aside from a single Lucy Dacus song. More likely the algorithm usually goes in the other direction—you start with Boygenius and end up with a hundred window panes.

When I look back and forth between Orla Gartland (who?) and Sabrina Carpenter, or BEL (huh?) and Julien Baker, or Caroline Kingsbury (…OK, this one I really like) and Chappell Roan, I don’t really notice the obvious differences that the algorithm seems to have sussed out. There must be something different about it: I could sense a difference when confronted with it in the wild. Still, it seems like a stream I should know better—there’s something so familiar about it, and then after following it for a while, I always realize I’m lost.

I recently revisited a piece that I think typifies the general “indie” sense of what sort of music used to be included in the term indie-pop—Nitsuh Abebe’s “Twee as Fuck: The Story of Indie Pop” for Pitchfork in 2005. “These kids, in their basements and bedrooms, were trying to hand-craft a mirror-image of [cool], a pop world where they were the stars.” The argument goes: in sounding like self-made stars, these artists—the C-86 UK indie scene and accompanying twee bands in the US—were drawing a line in the sand against an actual mainstream, which to them included the “cool kids” who parlayed the legacy of punk to the charts.

He was only off by one act (Neko Case). The top six finishers in the Pazz and Jop critics poll that year were, in order, Animal Collective, Phoenix, Neko Case, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Dirty Projectors, Grizzly Bear.

Some indie records sold pretty well before then. It’s interesting to look back to how well critically acclaimed indie did on the albums chart when it was released, though. Liz Phair’s Exile in Guyville, the #1 Pazz and Jop album of 1993, peaked at #196 on the Billboard 200. The highest Pavement ever got was #70 in 1997. Even an enormous early millennial indie hit like the Strokes Is This It only peaked at #33 on the albums charts—the eighth-best-selling new rock album in its peak week, below Creed, Linkin Park, Nickelback, P.O.D., Puddle of Mudd, Kid Rock, and Hoobastank.

This chart doesn’t adjust for inflation like the previous one does, so it’s not exactly the same heights. Streaming is also a very different revenue sharing model, so you need to imagine about 30% of streaming revenue going to the platforms. There is some evidence that streaming has plateaued and needs global expansion, especially in Asia, Latin America, and Africa, to maintain or increase these revenues (more on that some other time).

Even before the rise of streaming platforms, I was tracking something like the landscape of indie/pop through streaming precursor Pandora. Around 2009, I tried to build a station for a friend that played what I called “sophisticated girly pop”: I started with Annie, Goldfrapp, Ladytron, and Robyn, and within a few years layered in Grimes, Lorde, Sky Ferreira, and Charli XCX. (Early Lana Del Rey got a “thumbs down.”) The station also played a lot of upbeat 90s alt-pop (lots of Cranberries and Cardigans), mid-aughts pop hits (Nelly Furtado with Timbaland, September’s “Cry for You”) and often insisted on some contemporaries I didn’t know very well (Bitter:Sweet, The Blow). By the time CHVRCHES started showing up in 2013, the station was already moving in a direction that didn’t match the vibe but was building toward the current indie-pop sound.

I don’t want to oversell the significance of Spotify recommending something. Spotify algorithms are usually not as complicated as people think they are, and they can be good at recommending random stuff, like figuring out which songs that do not feature any Muppets still sound the most like the Muppets.

The first piece I remember on a topic like this is Liz Pelly’s 2018 piece on “streambait,” which described a different pop sound that was popular on Spotify without crossing over to the charts. My own take on this from the same time period was different from hers; I focused more on how Spotify was running a grand experiment in digital A&R that mostly produced weird counter-factual pop curiosities

This is a great exploration of what it feels like the 'hipster' of the mid-2020's would be talking about - so basically an article written for me!

Fascinating that conversations around genre/culture needs to include an understanding of algorithmic serving, economic and technological trends and so rarely ever does. A breath of fresh air.

I feel as confused as ever about the state of art and culture after reading this but in a way that feels energising rather than depressing.

I wonder if our evolving sense of genre and cultural movements writ large will need to include an understanding of their distribution technologically as an inherent feature of their definition.

Keep writing!

"At least ten or twenty tracks like it have shown up in my playlists each week for years." This is ambiguous. You mean ten to twenty have shown up in the playlists you *listen* *to* on Spotify, not the ones you make for us; but I actually interpreted it the second way until I thought, "That can't be true."