All installments Part 1 || Part 2

When I started applying the term “A-pop” to American-originating pop music, friends who were following along on this definitional journey had a lot of questions. The most frequent question was whether or not some artist or another qualifies. Is Taylor Swift A-pop? What about Benson Boone? Can non-Americans be A-pop? Can A-pop work retroactively—was Lady Gaga A-pop? Was Madonna or Michael Jackson A-pop? Was Elvis?

There are two things to keep in mind, one that I’ll write about today and another that I’ll write about more later. First, the subject for a future installment: I use the term A-pop to refer to a phenomenon that has developed over a time period of about twenty years. I think there is a pre-history of A-pop that includes older pop superstars, especially ones who came to prominence by about 2010, but I don’t know if it really makes sense to refer to them as “A-pop,” which describes a more recent shift.

It’s helpful to look at the inverse view of A-pop—not what happened to American pop music in the past two decades, but what happened everywhere else. For A-pop to exist, you need strong regional scenes that affect American pop the way American pop has long affected other countries, not just as influences but as equal or in some cases superior market competitors.1

The second idea to keep in mind is that the process through which pop music achieves any level of popularity follows certain universal principles of social diffusion. These principles now apply at a frictionless global scale that mirrors frictionless global access to streaming media. The result is more music from more places getting more popular much faster than was possible in previous eras of mass media distribution.

I think one side effect of this is that lots of American pop music that positions itself as part of an aspiring (or assumed) hegemon ends up seeming smaller, while other regional music forms seem comparatively bigger, including some forms in the United States itself.2 The stuff that plays at bigness but seems small is definitely A-pop; the stuff that actually hits big might be A-pop, but it might also be characterized as something else.

There are still a lot of American and western Anglophone music acts who bypass the pitfalls of this potential smallness and get world famous without feeling tethered to an obvious style or scene, even if they started in one. I think this broadly describes Taylor Swift and Drake in the first half of the ‘10s and The Weeknd and Post Malone in the second half. It may also describe Morgan Wallen, Noah Kahan, Benson Boone, or Jelly Roll now.

But there are some trickier cases. Like, what’s the deal with Teddy Swims?

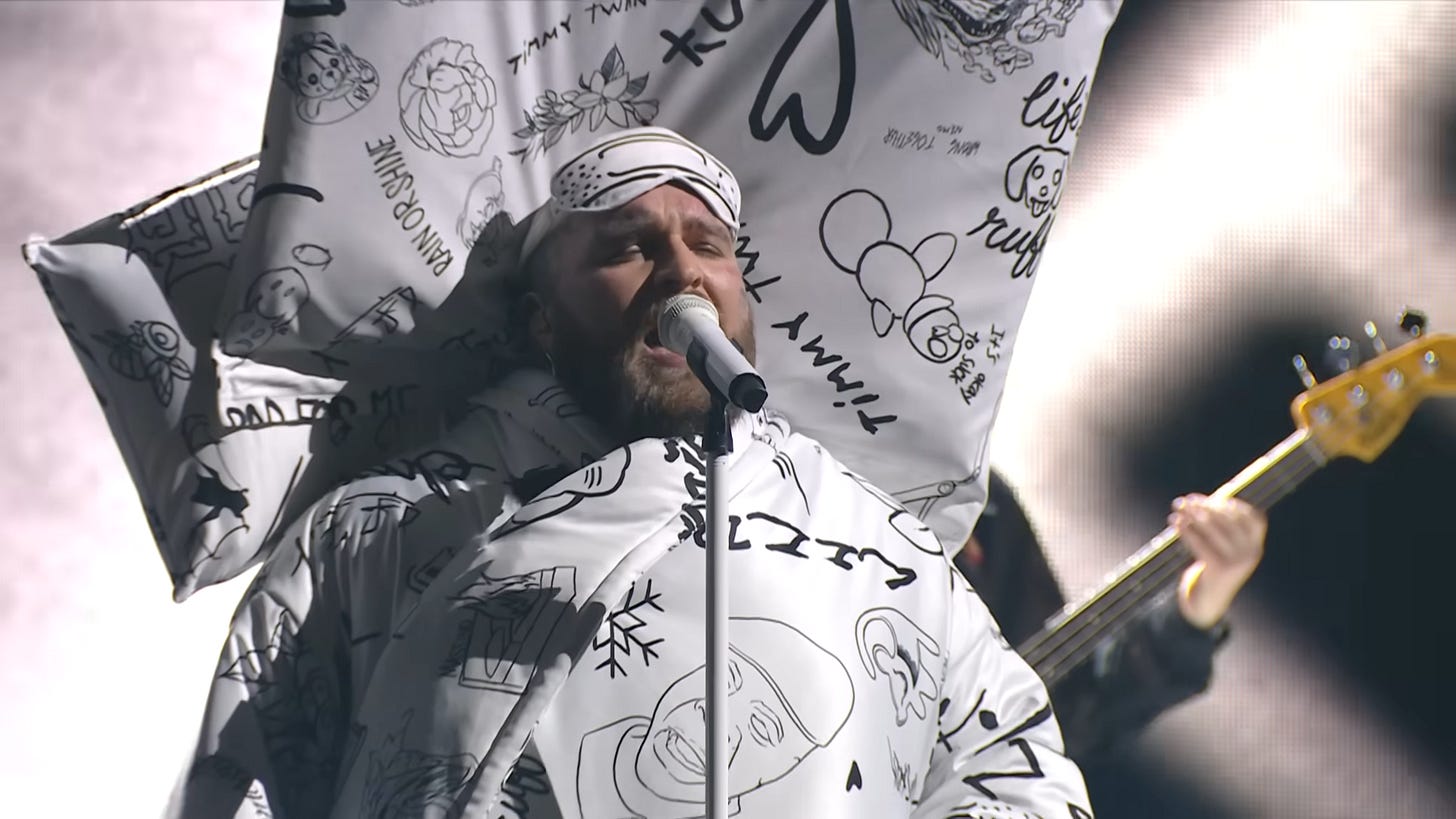

My friend Holly Boson has provided the most constructive pushback to A-pop as a concept. I made a claim to her recently that seeing Teddy Swims dressed as a bed at the BRIT Awards (pictured above) suggested to me that Teddy Swims is not A-pop. This was a purely intuitive claim on my part, but her response was clarifying:

“To me he’s neck deep in what I assume A-pop is—syncretic nonspecific American pop where it’s not really any genre and doesn’t come with a story.”

This phrase, “syncretic nonspecific American pop,” has been rattling around my head for weeks now. I wouldn’t say this is an inaccurate description of music I’d call A-pop by any means. But, to use that inverse way of thinking about the A-pop phenomenon, this phrase also describes massively popular acts from a variety of genres and regions, many of which are represented in charts like the Billboard Global 200 and also find their way to the public spaces I encounter in the US: restaurants, shops, playgrounds, car stereos.

I think the synthesis posited in this observation is a better description not of a coherent regional pop scene, but of the product of fierce musical competition at a massive scale: globalized streaming-era cumulative advantage.

Cumulative advantage is the social process, demonstrated in experiments and popularized by sociologist Duncan Watts in the mid-aughts, whereby something that has gained some popularity is inertially inclined to continue gaining popularity: “the rich get richer.” It is the mechanism at play when something goes viral. The technical term for “viral” used in this literature is the “cascade”: the popularity of something snowballs as more people share it and, importantly, as more people observe other people sharing it.3 You may or may not like what your friends and the people around you like, but you will almost certainly notice it, and any mass adoration is conditional on mass attention.

The profound mystery of cumulative advantage is that even though accumulating the advantage is simple and predictable—the more people notice and like something, the more other people notice and like something, too—the initial spark for the cascade, the thing that gets the snowball rolling, is fundamentally unpredictable. What seems like a pat post hoc explanation for a thing’s popularity is unknowable before the process begins, and totally subject to chance. Crucial early events—the right timing, the right news story, the right live appearance, the right high-profile recommendation—have an outsized effect on future success. But you cannot ever know in advance which early events will lead to a cascade.

Popularity at any scale, from a schoolyard chant to an international pop music success, works on principles of cumulative advantage—“the rich get richer” is something close to an iron law of social physics. When popularity cascades are truly transnational, and something huge in any part of the world may cross over to any other part of the world, then the field for how many super-snowballs can coexist expands.

This is something like the opposite of the complaints of mid-’10s “blockbuster pop” analysis, which focused on how a huge percentage of entertainment coverage converged on a dwindling number of megastar artists. I would argue that this apparent dwindling really only happened because the outlets in question were only focused on a single region, and often a narrow sense of what counts as pop even within that region.4 I believe these complaints were circling around, without naming, the transition to A-pop, the development of a scene that looks smaller against a new landscape of outsized exceptions.

It seems true that within a scene or a region or more vaguely a “lane,” the process of globalized cumulative advantage is cutthroat and all but zero-sum: there’s only one Taylor Swift, so no one who is like Taylor Swift can meaningfully compete at anything close to her scale.5 But there’s also a Bad Bunny and a Blackpink and a BTS, too, and that’s only the beginning of the alphabet.

I describe this landscape of global superstardom as a monsterverse, after the Godzilla and King Kong cinematic universe. Like the kaiju of the movie Monsterverse, each creature has its own unique backstory, even if some creatures may bear a family resemblance to others. For the most part, they have a clear lane and you can’t confuse them, and you don’t have identical characters competing. (You can pit King Kong against Godzilla, but the results are much weaker when you pit King Kong against “King Kong, but smaller.”)

So who can compete in the monsterverse? That’s where the unpredictability of cumulative advantage is important, but frustratingly tautological: it’s anyone who gets big enough. The pop monsters may have synthesized major elements of a region or genre, or may exhibit some other characteristic from a local scene or audience, or may have just capitalized on a random spark of an initial popularity cascade. The sparks seem endless: a personality type, a huge viral song of the moment, an even more stochastic fluke like TikTok success, or some combination of all of these.

In some examples, this looks like the pulling away of clear winners from a competitive group of large but not yet super-sized combatants: BTS and Blackpink “won” the boyband and girl group K-pop landscape, respectively, in the same way that Taylor Swift “won” the landscape of teen pop’s adult contemporary turn.6

In other examples, you get a representative synthesis of an emerging scene where other artists for the most part aren’t operating on the same scale. This has happened a few times in different African and Latin American scenes, like Burna Boy from Nigerian Afrobeats, Bad Bunny in Puerto Rican music, Bizarrap in Argentine rap, Anitta in Brazilian pop and funk music, El Alfa in dembow, Peso Pluma in regional Mexican music, or maybe one of the burgeoning South African house or amapiano stars.7

That brings us back to Teddy Swims, and why I sensed he’s not just A-pop: he might be a monster, too. Perhaps Teddy Swims comes from something like a “scene”; in his case it may just be one of the many calcified corners of millennial pop music ripe for periodic revival for the foreseeable future — a sort of sclerotic neo-soul that was inescapable going into the ‘10s and will probably remain inescapable until the millennial generation’s echo baby boom loses its grip on pop culture. Or maybe he came from nowhere, or, to paraphrase Duncan Watts, he came from nowhere obvious until you already know the answer.8

I want to be clear that popularity has always worked this way, with cumulative advantage serving as the engine to exponential attention and the development of huge pop personalities, many of them at least eventually global in scope. Again, what’s different is a shift to a wider omnidirectionality—there are more regions with more claims to a local mass culture crossing over into a global mass culture, and the crossovers can happen in a span of weeks or months instead of years.

One curious thing I’ve been reflecting on is that the new monsterverse stars tend to leave me colder on average than their hardscrabble counterparts. I wonder if something about succeeding in the current competitive environment requires a synthesis—a set of compromises—that feels less like capturing the lightning of a moment and broadcasting its promise to the world, and more like an averaging or flattening out of the many sparks of potential on the ground.

But that doesn’t sound right. More likely, it’s not really about the monsters at all, but about those of us down here on the ground. I have always had an insatiable drive to find my next favorite artist, and I now have constant, immediate access to unthinkably large fields of music, a privilege which allows me to make finer distinctions than I ever could have made when so many artists below a certain popularity threshold were effectively invisible to me. There is an exciting sense of potential in the sheer volume of interesting non-monsters that I can (and usually do) focus my own little beacon of attention on instead. Some day they might get their ball rolling, too, and do some real damage.

There are historical comparisons in other popular media. To pick one example that I observed personally in my childhood, Japanese animé began competing seriously with American animation in the 1980s, and was a dominant (maybe the dominant) animation style by at least the 2000s if not sooner. I won’t claim to know much of anything about animé because unlike my friends, I never really watched much of it. But I think that puts me in a stronger position to make this claim, because that means it was totally unavoidable in my childhood the way that K-pop is unavoidable in my kids’ childhood today.

I think this is one of the factors of country music’s recent world-wide expansion, with the secret ingredient being its full sonic embrace of rap to bring it more in line with pop that tends to travel internationally. Why hip-hop (and jazz and blues and rock before it) traveled so well is a good subject for a different post, one I may or may not be qualified to ever write.

I prefer the somewhat clinical “popularity cascade” to “viral” because the former term is more focused on what happens to the audience, whereas the latter term gives too much weight to the object. At some level every song is a virus; how it spreads has more to do with what happens in the audience than the features of the virus itself, though those obviously aren’t irrelevant.

The usual gripes were about Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, Drake, and sometimes Rihanna. But this ignored a lot of huge American, British, and other anglophone artists that didn’t fit a particular style of coverage, i.e. they slotted uncomfortably into “pop music.” Eminem remained enormous through the ‘10s, at a comparable level of sales as anyone else in the blockbuster pop club, but commentary on him wasn’t anywhere close to as extensive as the other superstars. Coldplay wasn’t far behind as the biggest 21st century rock group. Ed Sheeran has been the biggest male singer-songwriter in the world for a decade now and I don’t know of very much serious critical engagement with him on a par with Taylor Swift.

This hasn’t always been true. E.g., in the previous era of millennial teenpop, there was always the question of who is the best version of a template—boy band, girl group, solo singer—which was a constant source of conflict among fans and on the charts. But in some periods it is true, as it was in the ‘80s “blockbuster pop” era of Madonna/Michael Jackson/Prince.

This is what I argue Taylor Swift did in the late ‘00s in my Swift series, anyway—steamrolled the entire competitive landscape of teen-oriented confessional music in a moment of relative decline and became its sole representative.

Amapiano is a uniquely collaborative scene, with producers getting credit seemingly for being in the studio at the same time or offering a suggestion or providing inspiration, so it would make sense that determining a popularity “breakthrough” would be difficult, or wouldn’t even happen (that is, “breaking through” would also mean just breaking, diverging from the amapiano scene proper). From what I can tell, there have been at least three semi-breakthroughs, each of which is a little different. Tyla blended the amapiano sound into Americanized R&B and achieved some success on US and UK charts, but she isn’t integral to the amapiano scene in South Africa and hasn’t proven to be an enduring success yet beyond “Water.” So far she reminds me more of Psy’s role in K-pop with “Gangnam Style” than the subsequent breakthroughs of Blackpink or BTS. Major League Djz have collaborated with tons of international producers, but not in a way that feels organic to the rest of the scene’s superproducers. Zee Nxumalo is probably the closest thing I’ve yet seen to a potential breakout vocalist — a true amapiano pop star — but her career is still very new. Two other options for a snycretic nonspecific South African star not directly from the amapiano scene would be Moonchild Sannelly or Sho Madjozi, who both seem much more omnivorous in their approach to pop.

There are other late-aughts monsters afoot. Noah Kahan is filling a role like this for the clap-stomp-hey boomlet. Benson Boone seems to fill this role for American Idol pop competing for space on American heartland superstore CD racks. I suspect that Sabrina Carpenter and Olivia Rodrigo are simultaneously A-pop and monster, like top-tier but sub-Blackpink/BTS K-pop groups: neither has really outpaced their “scene,” their positions are strong but in flux, and Taylor Swift is still lurking like a final boss.

The best question I ever saw asked on music twitter was, where is there a black artist who sounds (or feels) like Lana Del Rey? Given how many imitators Lana has in all directions? The tweeter named Baby Storme as the only possible example she could think of, and I can see that, if Lana had taken a witchouse turn at Honeymoon.

This question haunts me.

Where would K-pop groups other than BTS and Blackpink fit in this? Stray Kids are huge, with several albums hitting #1 in the U.S. and going gold, but they still somehow seem outside the American mainstream.