How You Get the World: Reflections on Taylor Swift, Pt. 1

Part 1: Taylor Swift surveys the wreckage of the late aughts and fancies she'll build an ice castle on top

Did you ever hear about the girl who got frozen?

All installments: Part 1 // Part 2 // Part 3 // Part 4 // Part 5 // Part 6 // Postscript 1

Queen Elsa is the most important fictional pop culture figure of the last decade easy, and not only because she was the only major franchise character to successfully combine the logic of the superhero movie with the heart of a Disney film and still find room for alienation and pain and the sudden white-hot urge to kill a man with an icicle through the eye socket because he got too close.

Elsa could conjure her whole world from her fingertips — she was the fairy godmother and the damsel and the prince and the witch. She consolidated the tropes, built her home and her power and identity — there was no distinction between these, for a time, when she was singing her song, anyway, when she let it go — out of infinitesimal shards of ice in the tundra. She walked into a frozen expanse and built an empire.

This is a series about Taylor Swift. It starts in 2006 and ends in 2008. We’ve been living in Taylor Swift’s 2008 for 15 years.

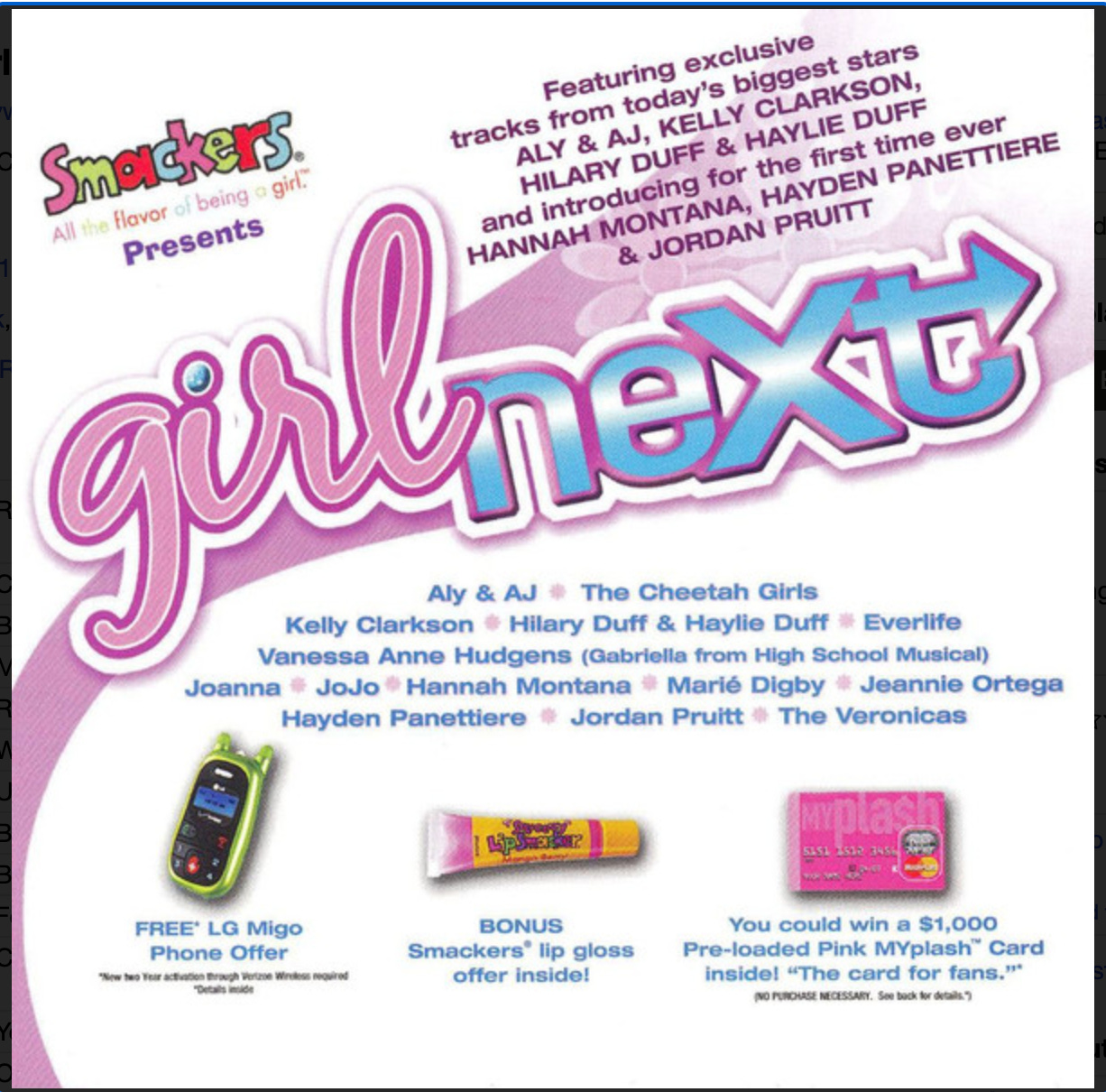

Taylor Swift walked out in what not everyone realized was a wasteland with her guitar and a somewhat unfashionable Nashville dream and figured out almost immediately that that wasn’t going to work. You could almost hear her chafing at the confines across her self-titled debut, where I immediately marked the structures of what I was then calling teenpop-one-word in a column in Stylus Magazine. I wasn’t yet imagining that maybe she would save teenpop, which was dying at the time, but figured by 2007 she was “a possible future for angst”: Radio Disney had bet everything on its homegrown programming, the mainstream label investment on rock confessional imploded like Ashlee Simpson’s voice on SNL after an acid reflux attack,1 and the energy was moving to house beats infiltrating R&B and burgeoning EDM crossover, sounds to which most of the confessional stars were ill-equipped to adapt.

But at the time you also wouldn’t play dance music in Starbucks or in the supermarket or the pharmacy. There was still the nebulous and functionally important umbrella of adult contemporary to fill the commercial spaces of our lives, and adult contemporary was the secret home base of what I and a couple other critics were then calling confessional teenpop: an amalgam of Lilith Fair lilt, post-Alanis Morissette alt-rock, and just a hint of coffee shop jazz. We were imagining one roof to house all those casualties of 00’s media — terrestrial radio, Total Request Live, print magazines, weird crosses between candy and lip gloss.

Teenpop-as-one-word was itself repurposed from its earlier form describing millennial pop music, your Britneys and Backstreets, among alt-weekly types in the Chuck Eddy-edited Village Voice music section. It was a word that attempted to describe the tentative resting place for lots of intertwining sounds and social strands and people — usually reckoned to be young people, averaged out in popular imagination to “sixteen-year-olds,” but often much younger than you’d think (the cap of Radio Disney’s demo was 14) and much older too, and not just from weird music critics. When I finally saw Ashlee Simpson in the waning days of her whimper of a post-SNL tour, the crowd was equally split between 12-year-olds, their 40-something parents, and college students.

The landscape for teenpop sucked; you needed to invent a word for it and track it across the most unreliable online media formats, or, even worse, the most obviously terminal non-online formats. You’re more likely to get working Geocities pages for flan recipes (ha, I knew that would work) than figure out what was going on on the Radio Disney charts between 2003 and 2007.

There was absolutely no indication that country music would fill the void, sure, but the most likely void-fillers — dance music, hip-hop, R&B, “grown up” weirdo pop stylings on the Hot 100 from former Disney stars — weren’t as obviously ascendant as you’d think. (If I’d been setting the odds at the end of the aughts of a Nickelodeon star being the huge neo-teenpop breakthrough of the next decade, I’d owe you my house now.) The specific problem with country music filling that void was the strength of its own old-school gatekeepers — it had a much stronger hold on its airplay and its charts and its sense of who belonged. Adult contemporary and Hot 100 always relented to audience pressure and went where the numbers took them, even if it was reluctantly.

So in hindsight it makes sense that Taylor Swift would eventually wind up outside of country music. But in 2006 it’s not like there was some other, obvious place where she would go instead. What seemed most likely from my perspective was more or less what happened to Ashlee Simpson, minus the reflux scandal: one stunning debut, a strong follow-up, a weird third album, and then a fade-out.

What Taylor Swift figured out, whether it was monomaniacal savvy (wouldn’t put it past her) or by some cosmic stroke of generational luck (also true; you can have both!), was that all of the pretty songs had to go somewhere. That uneasy bundle of youth energy and adult sensibility that had been shuttled between dying formats for almost ten years — watch Ashlee Simpson go like a hot potato between Radio Disney, MTV, and then finally land with a single song, “Pieces of Me,” enshrined in adult contemporary eternity in a vitamin store near you — had to land somewhere eventually.

I figured it would land on a format, on a genre, on a scene. But it landed exclusively on Taylor Swift.

Taylor Swift is who she is now, in part, because by 2008 the whole world of music had frozen over, and she was the one person who was smart and/or lucky enough to consolidate every trope, buy every format for pennies on the dollar, and build herself an ice castle.

I’m not a truther, folks, we all saw the footage.