How You Get the World: Reflections on Taylor Swift, Pt. 6

The end of the American popular music era

You said there was nothing in the world that could stop it

All installments: Part 1 // Part 2 // Part 3 // Part 4 // Part 5 // Part 6 // Postscript 1

Note: This is the final installment in my Taylor Swift series (for now). If this is the first one you’re reading, I encourage you to read the others. You don’t have to read them in order.

Taylor Swift just successfully completed her biggest year to date, nabbing the title of TIME’s person of the year as a feather in her cap. But don’t be fooled into thinking that 2023 is anything special—Taylor Swift’s career trajectory has been steady since November 2008, a thought that the timid TIME interviewer almost points out to Swift in person, but decides it will scan as too confrontational.

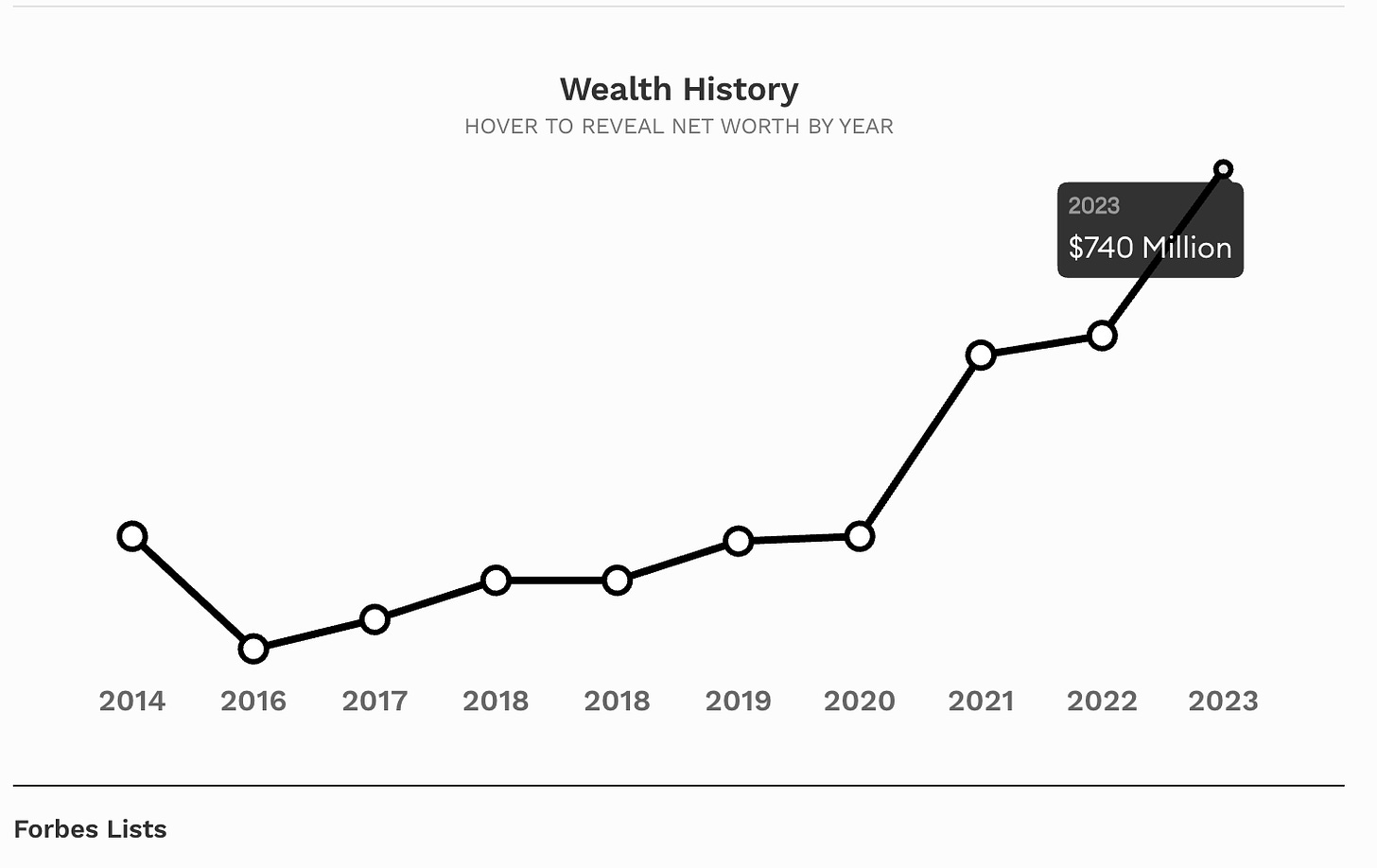

You can check in on her Public Narrative in any number of serviceable to good profiles at any point and see it intact, as shelf stable as a Twinkie: 2008 in the New York Times. 2009 in Rolling Stone. 2010 in New York Magazine. 2011 in the New Yorker. 2012 in Vogue. 2013 in Vulture. 2014 in Vanity Fair. 2015 in GQ. 2016 in Vogue (again). 2017 in Billboard. 2019 in Rolling Stone (again). In the pandemic years her wealth rapidly doubles,1 after which she emerges for her biggest profiles yet in 2023, in the New York Times and, of course, TIME.

The story is always the same. She is preternaturally gifted. She works really hard. Was on the Nashville grind at age 13, caught the ear of Scott Borchetta and got a unicorn record deal with Big Machine, won over hordes of young fans, then cannily “matured” and “went pop” as her work ethic only got more laser-focused on doing…whatever it is that Taylor Swift does (no one is particularly clear on what this is). Dated famous people, but it’s not really about that, except when it is. Survived any attempts to disparage her, which are recounted as major obstacles but read like extremely minor occasional celebrity skirmishes well within the normal range of celebrity interactions. She doesn’t provide a ton of access, and when she does, she usually sounds “handled,” but not by any handlers (it’s part of her brand savvy), leaving writers to fill in a lot of, er, blank spaces.

There are precious few high-quality critical interventions into Taylor Swift’s narrative, which was established fully-formed in 2008. There are a scattering of illuminating profiles and interesting interviews, and there are reams of analysis of everything around Taylor Swift: conversations about her style and her fans and her money and what she means in terms of related social themes and news pegs. (As far as I can tell, there are zero good books written about her.)

Because so many of her detractors have been so cartoonishly ignorant about the contours of her music and career over the years, they have long been trivially easy to dismiss: feminist blogosphere bullies c. 2010-2013, axe-grinding anti-poptimists c. 2014-2016, disappointed fascists c. 2017-2019. (After that, most of the critiques stopped altogether.)

The best star image analysis of Taylor Swift I’ve ever read is from back in 2013, when Tess McGeer did a One Week One Band series on Swift just after Red was released. It is remarkable to revisit it now and realize that almost no one has written anything even remotely close to as good as it, let alone better than it, even as her fame has steadily grown. It’s a great series, but Taylor Swift has consistently been the biggest celebrity musician in the world for fifteen years. It seems impossible to me that I am approximately two degrees of separation from sending a text message to the majority of people who have written interesting criticism about Taylor Swift.

You’d think there’d be a thriving critical conversation about Taylor Swift’s music, not just the mere fact of her existence. But this misses something important about how Taylor Swift won the world. It would be a mistake to think that there is something so unique about Taylor Swift as an artist or human being that this alone would explain not only why she is so immensely popular, but why she has had no meaningful competition since 2009. Her savvy and skill may account for much of her popularity, but not for running the table.

I started the series comparing Taylor Swift to Elsa from Frozen, and I want to bring it full circle, to the erosion of US culture industries over the past twenty-plus years. Taylor Swift is not only like a Disney property metaphorically; she is literally pop music’s embodiment of winner-takes-all corporate consolidation in a fragmented media and attention environment. She is the last American pop star standing, and there will not be any others, at least not like there used to be.

If you look at lists of the biggest-selling music stars whose work was entirely or almost entirely released in the 21st century, you’ll usually see that Eminem and Taylor Swift rest comfortably in their own VIP section, hobnobbing with the Beatles and Michael Jackson and Madonna and Elvis, along with 80s and 90s superstars, AOR dinosaurs, and decades-long perennial bestsellers.2 Below those two, you’ll find an ambiguous megastar tier that includes Drake, Rihanna, and probably Beyoncé, and if you squint might extend to Britney Spears or Coldplay. After them, you’ll finally get into the “normal” world of rarified A-list pop stardom, where it’s harder to sort things out and the numbers are more contested: Justin Bieber, Ed Sheeran, Adele.

Eminem has his own story, part of which is his massive success during the CD boom. There’s more to his story, including how resilient his sales have remained after critics all but abandoned him in 2004. But Taylor Swift’s initial rise happened long after the CD boom, between 2007 and 2008, and her chart dominance was locked in by 2010, around the same time Drake accomplished the same thing in hip-hop.3

Remember: Taylor Swift consolidated the entirety of teenpop culture—everything running the gamut between 4-year-olds and 40-year-olds through Radio Disney, Total Request Live, and adult contemporary radio—in a span of three years, and was the subject of gobsmacked analyses of her outlier record sales as early as 2009.

Anyone who could hope to make a comparable dent on sales charts for the next 20 years would need to be locked in by 2010, before the shift to the streaming era. In 2014, Vox helpfully wrote a “Taylor Swift is an asterisk” explainer that points out that 2014 was the historical nadir for album sales, one from which no one has recovered. On top of any savvy career moves they made after 2008, Taylor Swift and Drake were both beneficiaries of powerful incumbent advantage as the rest of their field withered away.

This isn’t hard to understand when you zoom out to other culture industries. Music isn’t the only casualty of the widening of global online access and shift to ubiquitous, on-demand streaming media. Most forms of US-dominant 20th century culture—its popular music, cinema, journalism, and television—have fragmented in roughly the same ways over the same period of time, and in so doing created openings for behemoths to consolidate audiences. Taylor Swift is simply to music what the Marvel Cinematic Universe (launch date: May 2, 2008) is to cineplexes.

This may be one reason that no strong critical assessment of her ever seems to find much of a foothold: without any meaningful competition, coverage takes predictable forms, just as it does for the Marvel movies. The business press benignly notes a thing’s cultural and economic ascendance or occasional missteps. Most of the remaining hint of a critical arts establishment doesn’t bother to poke at fandoms, and either shies away entirely or positions itself more comfortably “inside the tent.”4 A few people may provide reactionary-seeming responses that wind up seeming both strident and ineffectual, like various auteur directors’ ongoing pseudo-feuds against the Marvel movies. This latter move is what has characterized the vast majority of the worst Taylor Swift critiques over the years.

But there is also the counter-example of television, which has not followed the path of incumbent advantage, in part because its erosion started much earlier. Television eroded in several stages between its peak audiences in the broadcast era and the withering audiences of the streaming era (namely via the fracturing of the cable transition from 1980-2000 and then gradual “untethering” from cable in the 2010’s).

Television is a reminder that there are two different ways fragmentation plays out. Cinema and pop music provide one example, where an incumbent whose big break happened at the tail end of the previous era leverages that enthusiasm into 20 years of unquestioned sales dominance: that’s Taylor Swift and the MCU. But television is a fragmented medium without an asterisk superstar, a field where no one powerful incumbent ever really “wins” and the rewards continually thin out, even as people have more options than ever, many of them at a level of quality unheard of in the era of blockbuster television.

The examples of television and cinema help clarify two things:

(1) Taylor Swift didn’t have to happen — there didn’t have to be any exceptions to the audience fragmentation and economic splintering of popular music.

(2) Once Taylor Swift did happen, it became almost impossible for any other music to compete with her precisely because the fragmented environment is what made her domination possible. Her success is itself a sign of the death of the whole field, not some weird exception to it, and certainly not its cause.

One reason I don’t believe it’s that fruitful to do elaborate analyses of Taylor Swift’s aesthetic and business decisions after 2008, is that the simplest explanation for her continued dominance—that she climbed to the top during the last possible era in which there was such a thing as a “top”—makes a lot of further analysis marginal. It would be like explaining how Amazon “stays on top,” or how the Marvel movies “stay on top,” when the reality is that they too haven’t had serious competition in many years, and it’s not clear how a start-up or previous incumbent would even begin to challenge them. My sense is that people keep trying to explain all of Taylor Swift’s choices because they find her tea leaves more interesting to read than the other two celebrities, Eminem and Drake, who have also coasted on their incumbency to a private tier of celebrity status.

The ingredients you need to understand what Taylor Swift owned exclusively by the end of 2008 are sitting ripe for real examination, but they aren’t discussed much. Taylor Swift was not just a country star who happened to make the move to pop music. She became the sole embodiment of the entirety of a once thriving economy of youth-oriented music culture whose distribution platforms all cratered at the same time. She is specifically the endpoint of teenpop music — including the turn of teenpop to adult contemporary formats in the mid-00s. The reason Taylor Swift can be an artist for children who also keeps appealing to adults at the same time, across multiple generations, is that teenpop as a cultural force had already made this move. Taylor Swift inherited it (she didn’t even really take it—no one tried to stop her!), and then the door closed.

What’s happening now, if you remove those asterisks of our superstars and think about the fragmenting ground beneath them, is the rise of regional music as formerly meaningful global distinctions blur or disappear. Every year brings a new story about so-called “regional” music appearing on previously US hegemonic charts: this year it was Mexican regional music, a few years ago was Nigeria’s time to shine, before that it was Spanish-language music from Puerto Rican artist Bad Bunny and Colombian artist J Balvin, and before that was the K-pop “invasion.” Some of these so-called regional artists are probably destined to outsell a lot of high-performing US artists—in some accounting, K-pop group BTS has already eclipsed just about everyone outside of the Taylor Swift tier. They also mark the end of US dominance as a global force of pop music, and perhaps the acceptance of America’s role as just another region competing with everyone else.

Globally, popular music is thriving—there is more of it than ever before, and much of it is incredible, and it has never in human history been easier to hear it all, hundreds of hours of it released on a daily basis. But the US is no longer an unstoppable cultural force broadcasting its stars and its sounds and its values to the rest of the world. That era is over; we’re all just waiting on Taylor Swift to finish her run.5

The end of Taylor Swift’s era, the symbol of the end of American pop music as synecdoche for global pop music, is uncertain. Marvel might be providing a glimpse of her future: a gradual overextension, relative sales erosion, and a mass sense of everyone (read: casual fans) being sick of the project, with a core of diehards keeping things high-selling but the extended universe losing its luster of untouchability. In that event, Taylor Swift would “settle” into being an A-list star who outsells everyone else but no one talks about much: a mere Sheeran.

A few things probably won’t happen:

Taylor Swift will not be “dethroned” by another American artist.

Barring a major scandal (politics, drug use, cult shit, a long string of extremely bad movies), her status as a sales leader won’t diminish much until she decides to stop making music (the Rihanna story), even if her general cultural status according to cultural commentators and magazine profile writers ebbs (the Eminem story).

Once Taylor Swift is no longer #1, there won’t be a #1 to return to, and it will be clear to everyone, if it wasn’t already, that pop music as an American art form is now a geeky, small-potatoes niche format like comics and theater, not a transnational commercial concern.

The choices, chances, and quirks of fate that made Taylor Swift’s 2008 a reality are not replicable. You can attribute a lot of things to both her successful launch and her subsequent trajectory: lots of savvy, lots of luck. But the one thing you can’t do is turn back the clock and make her not happen, and once she happened, there was no stopping her. She got the world: a world that no longer exists, and will probably remain hers until whenever she finally decides to let it go.

There are lots of ways to account for the best-selling music acts. Some methods give more misleading numbers than others, and the lists tend not to agree with each other. I’m giving a general sense based on how artists appear on different variations on these lists, so will group lots of artists together in the “A-list” that may be higher or lower than other people on that list depending on how you account for their music.

Rihanna is a subject for more research, and she may be equivalent to Drake in a different lane of pop and R&B. I find that accounts of her sales vary more than Taylor Swift’s: some calculations even put her in the same sales tier as Eminem and Taylor Swift, though this seems unlikely. Most lists put her in the leading position among pop and R&B stars like Beyoncé and Adele and Katy Perry, all of whom she has probably outsold. But it’s likely that she is still below Taylor Swift, and possibly Drake, in sales.

This is not to say “in the tank,” exactly. Critics have been generally positive toward Taylor Swift because she makes music worth being generally positive about, and we have musicians without comparable coverage (Drake and Eminem) to know that there’s no mandate to treat megasellers with kid gloves as a rule. I tend to think these sorts of critiques are overblown, and that we shouldn’t confuse the twin deaths of a competitive US pop sales environment and any remaining outlets for paid music criticism with some conspiracy of the remaining music critics to essentially lie about how good Taylor Swift’s music is. There’s just nothing else like her in the highest echelon of sales, unless you want to talk about Drake or Eminem, which critics generally don’t.

If you look at Eminem, Drake, and Taylor Swift as endpoints of an era of US pop music’s influence on the world, you have to wonder what exactly that influence was. One thing that has ended, I think, is the US export of its oppressive racial binary into new contexts, with blues and rock ‘n’ roll and hip-hop on one side of the binary, and country and singer-songwriter and indie rock and adult contemporary on the other. There are white artists and Black artists on both sides, but histories of these genres and movements often reduce down to racial essentialism: “white artists stole rock ‘n’ roll from Black artists”; “why is indie rock so white”; etc. In that formulation—which, to be clear, I’ve thought about but don’t necessarily agree with, hence this being tucked in a footnote!—Drake is the final gasp of “Black music,” Taylor Swift the final gasp of “white music,” and Eminem is the complicated Elvis figure somewhere in the middle.

FWIW my reasonably confident* guess at best-selling 21st century artists using a literal definition of sales (no distinction between albums/singles or physical/digital, streaming doesn't count) is 1. Eminem 2. Rihanna 3. Taylor, with RiRi having the advantage of her 2007-16 Imperial phase corresponding exactly with the iTunes era. Of course this mostly shows that pure sales isn't the best way to make comparisons even pre-streaming: for one thing live shows should count (it's the biggest revenue stream for Taylor among many others these days) though pure revenue also shouldn't be used too literally or you get things like Depeche Mode (!) being one of the biggest artists of 2023.

*We have pretty good approximations for US and Western European sales these days; Asia remains mysterious outside of Japan and maybe Korea